In the first essay of this series, I argued that the influence of G. K. Chesterton on Tolkien’s work is evident in the latter’s aesthetic scheme. Tolkien’s attitude to art, advocation of simple devotions and defence of fairy-stories mirror and build upon the ideas of Chesterton. These principles were most famously put into practice in Tolkien’s perpetually popular books, The Hobbit (1937) and The Lord of the Rings (1954-55). A large part of the success of these works was their choice of protagonists. Hobbits are distinctly modern English characters with their comfortable lives spent tending to gardens, smoking pipes and going to the pub. That Tolkien succeeds at so seamlessly integrating them into a high medieval fantasy is a credit to his ability as a storyteller.

In this second essay, I want to explore how a specific aspect of Tolkien’s context informed the representation of the Shire and its inhabitants in Book 1 of The Lord of the Rings. In particular, I want to explore how Chesterton, again, can be seen as an influence and how Tolkien instantiates a particular view of English patriotism in the Shire. Chesterton’s political outlook was characteristically idiosyncratic and remains an intriguing relic of a particular era of British history. That many of its features turn up in Tolkien’s representation of the Shire can tell us something about the Shire and Tolkien himself.

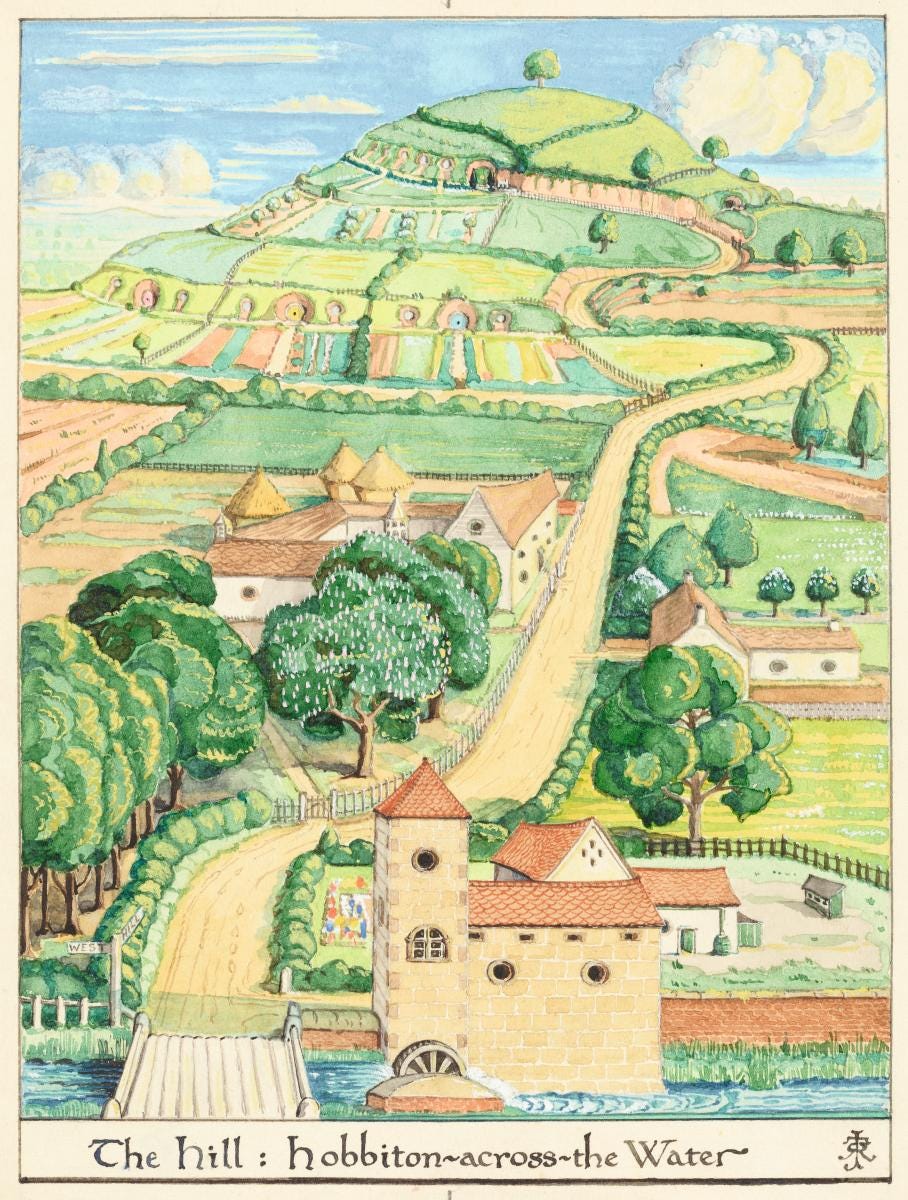

The Englishness of J. R. R. Tolkien and his work is an obvious fact to anyone who reads The Hobbit (1937) or The Lord of the Rings (1952). It is undoubtedly an essential ingredient in the works themselves and the self-image of the man who created them. Tolkien himself remarked:

'The Shire' is based on rural England and not any other country in the world [...] in much the same sense as are its inhabitants: they go together and are meant to. After all, the book is English, and by an Englishman1

His patriotism, such as it was, was both idiosyncratic and historically specific. While there may be “no special reference to ‘England’ in the Shire”, as Tolkien claimed elsewhere, we can still view his devotion to his childhood home in Sarehole and the Warwickshire of “about the time of the Diamond Jubilee” within a particular context of English patriotism.2 The bounded, local and refracted nature of Tolkien’s representation of England should not lead us to doubt that that is what the Shire is. On this basis a strong case can be made that the Shire, and its transformation, in The Lord of the Rings can be seen as Tolkien’s most complex and persistent commentary on his own country. The principles enshrined in the aesthetic view I explored in my previous essay animate and nuance that commentary.

A key aspect of Tolkien’s early-twentieth century context is so-called “Little Englander” patriotism. The term “Little Englander” has been an epithet since it was first used during the debates about the Boer War (1899-1902) however, its connotations have radically shifted since the end of the Second World War. If used today it is generally meant to describe a kind of reflexive, unworldly and uneducated jingoism; a reactionary rejection of the outside world based on a chauvinist nationalism. This picture is quite different to how the term was used at the dawn of the twentieth century. A modern Little Englander might be expected to sing “Rule Britannia” with gusto and vote for Nigel Farage, by contrast, the term was originally meant for people who criticized British imperialism in South Africa and voted for the now-forgotten Liberal, Henry Campbell-Bannerman. Those who willingly appropriated the label saw themselves as rejecting the conformist jingoism of many Tories and Liberals who thought criticism of the war against the Boers should wait until it was over; “my country, right or wrong” was the slogan. G. K. Chesterton’s pithy retort was that such a sentiment was tantamount to saying “my mother, drunk or sober”.3

The “Little Englander” tendency argued that British imperialism had undermined a true sense of Englishness. The alienating forces of capitalism, and the aggressive cosmopolitanism it enabled, had disenfranchised the common people, severing their ties to the land and each other. It is telling that the project of liberating English patriotism from loyalty to the Empire was a central concern of not just G. K. Chesterton but also George Orwell, a key contributor to English self-representation in the twentieth century. Of course, Tolkien himself had similar pre-occupations: “For I love England (not Great Britain and certainly not the British Commonwealth (grr!))”.4 They were all feeding off a long tradition of English romanticism which privileged the countryside over the city; the comfortable beauty of home over the dark and dangerous colonial frontiers.5 While not an anti-imperialist himself, Arthur Quiller-Couch provides an illustrative account of the link between the pastoral and a non-aggressive patriotism in a collection of essays published in 1918. For Q, the body of English literature has provided an education in “implicit” patriotism. Patriotism, he argues, is a strong strain within the English literary tradition but it is almost always found refracted by love of particular places; “the home and hearths now to be defended”. To find the wellspring of “true patriotism”, the Englishman must “seek home [in] a green nook of his youth in Yorkshire or Derbyshire, Shropshire or Kent or Devon; where the folk are slow, but there is seed-time and harvest and 'pure religion breathing household laws'."6

In some quarters the entire pastoral tradition is suspect. David Gervais argues in his Literary Englands (1993) that "The usual strategy of pastoral is to make the part stand for the whole” and the accusation by critics such as Raymond Williams is that this is a “partial and misleading response” which is complicit in “a direct opposition to social change, a reactionary clinging to a static present”.7 Additionally, the notion that Tolkien presents the Shire as a static “timeless idyll” remains a common refrain even among sympathetic Tolkien commentators.8 While there may be an element of truth in these positions I think they miss how preoccupied Tolkien is with the Shire’s limitations, its transience and its fragility. The Shire that is depicted in Book 1 of The Lord of the Rings is idyllic, but its beauty is accompanied by a subtle yet consistent reminder that it is not a permanent haven severed from the concerns and threats of the outside. By exploring the way Tolkien adapts the principles of Chesterton’s Distributism and utilises the tropes of “Little England” we can see how devotion to a particular place can live alongside recognition of its finitude thereby dispelling the claim that the Shire contributes to a kind of reactionary jingoism.

The Shire as an accident of history

In the front of The Lord of the Rings there is a rather curious sixteen-page prologue dedicated to hobbits, their history and ways. It provides us with a historical naturalisation which explains the source of the quietness, comfort, and security of hobbit lands which could be taken for granted in The Hobbit but becomes a matter in need of explanation in the grand historical scheme of The Lord of the Rings. The account provided is a repetition, elaboration and, in some cases, a slight clarification on the information we get in The Hobbit. Hobbits are a little people who lived “long ago in the quiet of the world, when there was less noise and more green”9:

[a] very ancient people more numerous than they are today; for they love peace and quiet and good tilled earth: a well ordered and well farmed countryside…They do not and did not understand or like machines more complicated than a forge-bellows, a water-mill, or a hand-loom…10

Intriguingly we also learn that while they arrived there long ago, the hobbits came to the land they now call The Shire after a long period of migration. The three “breeds” moved from the Vale of Anduin and came over the mountains for uncertain reasons. Eventually they came down from “the Angle” into Eriador and then into what became known as The Shire with leave from the King of the North Kingdom. As a brief aside, if you needed any further convincing that the Shire is in some sense a representation of England, and the English, then it is worth pointing out that this history closely mirrors the formation of England which was a blending of the Angles, Jutes and Saxons who also migrated from a region known as “the Angle”.11

It is at this point that they enter history proper because the hobbits’ own records commence with the foundation of the Shire. This transition between a mixture of anthropological speculation and oral tradition into “history with a reckoning of years”, provides an immersive account of how a “homeland” becomes established.12 This historical background translates the features of Tolkien’s aesthetic view onto the canvas of a society and the creation of a homeland. The features of sub-creation which I outlined in my previous essay are the same as those which define the Shire. First, the tools of creation are given as a gift; both the land and the language, the common speech of Men, used to create the Shire are given as gifts to the hobbits. As Aaron Jackson has noted, “[t]he prologue [….] does not narrate an origin of hobbits, but rather how hobbits and the Shire came to define each other as such.”13 A homeland is a constructed product of active participation, it is a combination of the “tongue and soil”.14 Second, these tools must be motivated by a simple and pure devotion to a thing for its own sake, “At once the western Hobbits fell in love [my emphasis] with their new land, and they remained there”.15 And finally, it must be allowed to pass on for others to enjoy. The scholarly tone with which the hobbits’ sub-creation of their homeland is communicated allows recognition of the Shire’s status as “an historical accident” to live alongside the emotional attachment with which the coming narrative will invite us to empathize.16 This reflects how Tolkien’s professional engagement with Old English literature fed his own attachment to his country and that tradition. The limitations and flaws of the Shire are never treated as counter points to the loyalty and devotion our characters feel for their homeland.

Politics and Distributism

The relationship between the Shire and contemporary ideas about Englishness is underlined when we turn our attention to the account the prologue gives of the Shire’s political apparatus, or rather, its lack of political apparatus:

The Shire at this time had hardly any ‘government’. Families for the most part managed their own affairs. Growing food and eating it occupied most of their time. In other matters they were, as a rule, generous and not greedy, but contented and moderate, so that estates, farms, workshops, and small trades tended to remain unchanged for generations17

There is the “Thain”, a hereditary title held by the Took family, which acts as something of a symbolic “master-in-chief” being “captain of the Shire-muster and the Hobbitry-in-arms” but the peaceful situation of the Shire meant that this was increasingly a mere title with little power. What law existed in the land was attributed to the King of the North Kingdom who had given hobbits leave to inhabit the lands which became known as the Shire.18 These were kept “of free will, because they were The Rules…both ancient and just.” This vague but firm constitutionalism is mirrored in George Orwell’s characterisation of the English in The Lion and the Unicorn (1940).

Here one comes upon an all-important English trait: the respect for constitutionalism and legality, the belief in 'the law' as something above the State and above the individual19

This generalisation is almost taken to the level of caricature in the Shire since there does not appear to be a State for the law to be above, it is more a set of solidified social standards enforced by conformity. There are the “Shirriffs” who are a small police service but they are “more concerned with the strayings of beasts than of people”.20 We learn in the prologue that hobbits have never fought amongst themselves and it seems that “never” should be taken literally because in “The Scouring of the Shire” we learn that a hobbit has never killed another except by accident.21 There are a number of other resonances between Tolkien’s representation of the hobbits and Orwell’s representation of the English. Among the characteristics they share are a love of flowers and gardening, a certain distrust of intellectualism, stubborn ignorance of the outside world, and an instinct for courage in times of crisis. Crucially, in the case of the hobbits, disinterest in the outside world is born of a contentment and comfort in the land they call their home, along with the security provided by the Dunedain, rather than a sense of innate superiority.

The Prologue, and the chapters that follow, place the Shire and its inhabitants firmly in the nexus of “ruralism, anti-industrialism, anti-capitalism, and anti-statism” which characterized much of the “Little Englander” camp.22 What is important to emphasise is that the hobbits of the Shire do not just evoke a kind of ruralist small-state liberalism but a particularly Chestertonian communalism summed up by the phrase “three acres and a cow”.23 The Distributist platform developed by G. K. Chesterton, his brother Cecil, and Hilaire Belloc in the 1920s and 30s hoped that an inducement to land ownership could bring about a de-centralisation of property which would ensure political liberty. While the similarly anarchic style of governance is suggestive, the significance of Distributism to understanding the Shire and Tolkien’s ideas lies in its attempt to re-orient the notion of ownership. Distributism was heavily informed by Catholic social teaching which sought to find a “third way” between socialism and capitalism.24 Chesterton remarked in his Autobiography that “what was called my medievalism was simply that I was very much interested in the historic meaning of Clapham Common.”25 The thesis underlying Distributism was that the result of the enclosure of common land and the consolidation of estates was a significant loss of political liberty as people were forced into towns and denied their self-sufficiency. The hope was that a recovery of the notion of the “commons” and an equality built on individual property ownership could shift the economy towards gift-exchange rather than the capitalistic dynamics of supply and demand.26 The resonance here can be clearly seen when we observe the traditions and norms of the hobbits. They give gifts on their birthdays rather than receive them and they delight in the joys of hospitality. Meanwhile, the “Party Tree” and surrounding glade do not appear to be owned by anyone.27 This echoes the claim of Chesterton and Orwell that English culture was built on things which were “communal but not official”.28 In Leaf by Niggle, the link between gifts and communal well-being was made when, upon seeing the tree, Niggle exclaims “it’s a gift”, and then comes to the realisation that “[t]his place cannot be left just as my private park”.29 This notion of the independence of the land is reiterated continually throughout the novel through characters such as Tom Bombadil and Treebeard (a subject I will be covering in more depth at a later date). That nature is not merely the property of one individual or reducible to its economic output is a key aspect of how Tolkien thinks about England and is partly the product of how he engages with Chesterton. It is partly the role of the English to be stewards of a land which will not always be theirs. Close to the beginning of the narrative proper the elf Gildor emphasises to our protagonists that “it is not your own Shire…Others dwelt here before hobbits were; and others will dwell here again when hobbits are no more. The wide world is all about you: you can fence yourselves in, but you cannot for ever fence it out.”30

It is true that the Shire is something of an ideal and an idyllic one at that, with its violent-less, generous and loveable inhabitants residing in its comfortable and scenic landscape. But we have seen how the prologue outlines the historically contingent nature of the Shire as an entity. It should also be noted that the hobbits themselves are also not presented without faults, their insularity manifests not just in suspicion of outsiders like Gandalf but suspicion of hobbits from other parts of the Shire!31 They can also be greedy, small-minded and malicious, perhaps best emblemised by the character of Ted Sandyman.32 In David Gervais’ treatment of William Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890), he argues that Morris “presents an ideal, that does not mean that it is idealised. It is less of an idyll than it seems.”33 Something similar can be said about the Shire, the descriptions of its people and landscape are meant to be attractive and “homey”, they are part of the Escape necessary to the story, but Tolkien continually confounds the notion that these attributes are immutable. In fact, I think it is central to the long arc of The Lord of the Rings that the Shire can only survive as the Shire as long as it is fought for, and renewed.

The worst of the poetry being written today is that it is too deliberately, and not inevitably, English. It is for an audience: there is more in it of the shouting of rhetorician, reciter, or politician than of the talk of friends and lovers. - Edward Thomas34

Ed. Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R Tolkien, Allen & Unwin, 1981. p. 250, #190.

Ibid. p. 235, #181.

G. K. Chesterton, “In Defence of Patriotism", The Defendant: Essays, Open Road Media, 2015. p. 59.

Letters, p. 65, #54.

David Gervais, Literary Englands: Versions of 'Englishness' in Modern Writing. Cambridge University Press, 1993. p. 8-9.

Arthur Quiller-Couch, Studies in Literature Vol I, Cambridge University Press, 1918. p. 301. One might add “or Berkshire, Warwickshire or Oxfordshire”.

Gervais, Literary Englands. p. 11. Patrick Curry, Defending Middle Earth, Tolkien: Myth and Modernity. HarperCollins, 1998. p. 45

Thomas Honegger, "‘The Past is another country’ – Romanticism, Tolkien, and the Middle Ages.", Hither Shore 7 (2010). P. 48. Jed Esty. A Shrinking Island: Modernism and National Culture in England. Princeton University Press, 2004. p. 122.

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit. HarperCollins, 2012. p. 5.

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring. HarperCollins, 2005. p. 1.

Tom Shippey, The Road to Middle-earth. Allen & Unwin, 1982. p. 77-8

FOTR, p. 4.

Aaron I. Jackson, Narrating England: Tolkien, the Twentieth Century, and English Cultural Self-Representation, Manchester Metropolitan University, 2015. p. 273.

Letters, p. 144, #131.

FOTR, p. 4.

Letters, p. 196-7, #154.

FOTR, p. 9.

Ibid, p. 9.

George Orwell, "The Lion and the Unicorn", England Your England: Notes on a Nation. Pushkin Press, 2021. p. 85-6.

FOTR, p. 10.

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Return of the King. HarperCollins, 2005. p. 1006.

Anna Vaninskaya, "Periodizing Tolkien: the Romantic Modern”, Ed. Stuart D. Lee, A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien. John Wiley & Sons, 2022. p. 358.

Matthew Taunton, "Distributism and the City", Ed. Matthew Beaumont, Matthew Ingleby, G. K. Chesterton, London and Modernity, Bloomsbury, 2013. p. 208.

Allison Milbank, Chesterton and Tolkien as Theologians. T & T Clark, 2009. p. 13, 127.

G. K. Chesterton, Autobiography. Hutchinson of London, 1969. p. 135.

Milbank, Chesterton and Tolkien as Theologians. p. 128.

FOTR, p. 27.

Chesterton, Autobiography. p. 312-3. Orwell, "The Lion and the Unicorn”. p. 77-8.

J. R. R. Tolkien, Leaf by Niggle. HarperCollins, 2016. p. 31, 34.

FOTR, p. 83.

Ibid. p. 93.

Ibid. p. 44-5.

Gervais, Literary Englands. p. 11. While it is not my focus here, William Morris was a big influence on Tolkien and it is known that he read News from Nowhere and other works.

Edward Thomas, et al, A Language Not to be Betrayed: Selected Prose of Edward Thomas, selected and introduced by Edna Longley. Garcanet, 1981. p. 281.

Having recently been in Serbia, the local sense of pride in homeland - without aggression or indulgence of vices - felt refreshing, which I'm sure owes something to the suppression it experienced under Soviet rule. I felt welcome there, was a great atmosphere to be immersed in. I can't say that England feels the same. It felt far closer to Tolkein's shire there than it now feels in parts of the UK for me, which to me highlights the timeliness and the need for this exploration. Well done!

Interesting ideas of commonality and also people recognising the “law” being above which is echoed in Daniel Hannan’s history “How we invented Freedom and why it matters”